DRC Medical elective: Week 3 - City of Joy and V-World farm

Jan 29, 2024

Hello everyone, it’s been a while since I’ve had the chance to sit down and write one of these again. Throw in the equivalent of stage 8 load shedding, some very dodgy Wifi and long clinic hours and you can hopefully understand why I’ve gone a tad silent lately. Nonetheless, I’ve been on some remarkable adventures I can’t wait to share with you all. Today I want to dedicate this post to Carlos Schuler and his wife Christine Deschryver.

Christine and Carlos are the founders of an extraordinary transformational community/program for women survivors of sexual violence aptly named City of Joy. Carlos runs a 300 hectare plantation called V-World Farm that helps sustain all the workers, volunteers and women at City of Joy. I don’t have the words to describe the pain and suffering that women have gone through in this country and would never do justice in explaining the miraculous transformations that happen at this center. I really urge you to watch the trailer to the award-winning documentary that tells the story of the first class of women at City of Joy, and chronicles the process by which such a revolutionary place came to be, from its origins with the women survivors themselves, to the opening of the center’s doors.

The award-winning film takes the audience on an intimate and inspiring journey. Since opening its doors, over 1500 women have graduated from program, women who have healed themselves, been nurtured, learned new skills, empowered themselves and together joined into a network of love and revolution.

I first got into contact with Carlos back when I started organising my medical elective. His father in law, Adrien Deschryver, was the founder of the Kahuzi-Biéga National Park with whom my parents worked with back in the day. Carlos took over the role of park director after his father’s passing. He also runs Coco lodge where I stay at here in Bukavu and has been a real “father figure”, making me feel right at home. We’ve spent many nights sharing stories and I’ve been fascinated by his accounts ranging from gorilla anti-poaching missions and civil war militia attacks to heartbreaking victims of genocide and rape which led them to founding City of Joy.

He graciously invited me to accompany him to work one day and I jumped on the opportunity. Dr Marie and I managed to wiggle ourselves out of clinic duty for one short morning and we eagerly set off not really knowing what to expect. Here’s how it unfolded:

We start the day off with a quick stop at City of Joy and Carlos takes us on an express tour of the facilities. Today marks the first day of a “new semester” for a group of 60 women who’ve come from all over the region with the hope of healing, becoming independent and self-sustainable. It’s almost impossible to imagine the horrors they have lived through when we are welcomed by open arms and heartfelt smiles. Carlos has asked me not to share pictures of the facility and to respect the privacy of these women whom are still very much at risk of ongoing violence in their native villages.

We jump back into the jeep and and drive down to the village of Nyanghezi, about 30 km South of Bukavu. Here lies a lush expanse of land that, in so many ways, feels like an extension of City of Joy. 42 graduates of the program and a further 200 workers are employed at V-World Farm and form a cooperative that tends to the land and trains participants at the City of Joy in sustainable farming methods.

Eight years ago, Carlos acquired the vast plot of land which spans 300 hectares of luscious green forest and fields. With very little agricultural knowledge but an unwavering vision, he transformed the plantation to what it has become today! 20,000 trees have been planted, a road has been built from scratch cutting through forest and marshland. An enormous warehouse building is up and running, with all the machinery purchased over the years from the revenues of their harvests. The plantation currently has hundreds of fields filled with rice, maize, sorghum and beans. 500 avocado trees are scattered all over the property with countless other fruit trees everywhere you walk. There are around 200 goats and sheep, 500 rabbits, 300 pigs and 50 large beehives. As if that wasn’t impressive enough, the farmworkers have engineered and created a 20 ton tilapia pisciculture!

Upon our arrival, we are left speechless as we take in the view of the plantation’s fields below the hilltop on which the warehouse and offices sit. Carlos has some work to attend to and one of the workers gives us a guided visit of all the facilities. He takes us through their large grainery, the 50-hive apiculture nestled in the forest and their 500 bunnies.

Once Carlos is done, we take the jeep down the hill to see the large hall they’ve built, together with three large communal houses where 42 graduates from the City of Joy program currently reside. Carlos and Christine are planning to hold a massive reunion for the 1500 previous graduates on the farm in the middle of the year to inaugurate their new hall.

The forested terrain packed with fruit trees suddenly opens up to endless rice fields as we make our way down the hill. It takes us a good ten minutes to traverse the 300 hectares until the numerous tilapia dams come into view. We park the car and are greeted by a hundred grazing goats and sheep. In front of us are 10 dams, each holding approximately two tons of tilapias. We’re in luck today as they are emptying one of the dams for their annual harvest.

This is done by pumping out all the water and steering the fishes towards their nets. They then meticulously sort two tons of tilapia according to size, releasing the juveniles and harvesting the adults to feed everyone at City of Joy and Coco lodge. The surplus goes to the farm workers or gets sold at various markets in Bukavu.

The process is very impressive as bucket after bucket is fished out and carried away in heavy basins. I join in the fun and help sort out my dinner for tonight back at the lodge!

Interesting cases at Panzi

There’s one case I haven’t been able to shake out of my head for the past week. I don’t think I’ll ever forget this 12 year old girl whom I admitted in the paediatric ward last week. I was called to examine young girl who was getting progressively short of breath and exhausted. Suspecting a cardiac issue due to her symptoms and some very loud murmurs, we decide to perform a cardiac echo. Unfortunately, we find a massive atrial septal defect (a congenital heart defect she was born with) now complicated by pulmonary hypertension and endocarditis. Surgical treatment is not even an option seeing as there are no paediatric cardiothoracic centers anywhere in central Africa and the paediatrician refuses to intubate a case without curative potential. The only thing we have left to treat her impending heart failure are diuretics and antibiotics. She is transferred to ICU during the night and I rush there first thing in the morning. I quickly realise we’re fighting a losing battle here and attempt to make her as comfortable as possible. I stay by her side until she takes her last gasping breath right in my arms two hours later. The sadness is unbearable and my frustration for this health system reaches an all time high. I muster up all the courage to inform her mother who’s just arrived at the hospital. The look on her face and the last breaths of her daughter will forever stay imprinted in my mind.

On a lighter note, some of you might know I have a passion for all things cardiology related. During my stay here, I quickly came to realise that both students and doctors struggle to analyse electrocardiograms (for the non-medical friends/family — the test that hooks you up to a series of electrodes and records the electrical activity of your heart by churning out a bunch of squiggles on a page). I discuss this issue with the Panzi cardiologist, Dr Kikuni, and propose to give the student interns a lecture on the topic. Dr Kikuni is delighted and admits that this is a major issue throughout the hospital. He one-ups me and suggests I create a three-part lecture series for all the interns and doctors in the internal medicine department! Luckily I have just the right person to call. My good friend Dr Viljoen, a senior cardiology registrar at Groote Schuur hospital, kindly allows me to use his undergraduate lecture material on the topic and I spend the next couple of nights preparing the lectures. I luckily already translated most of the content last year while working on the French version of ECG APPtitude.

Thursday rolls by and my lecture is scheduled for the morning prior to the ward rounds. All the student interns and internal med doctors are packed into a small room and my lecture goes off without a hitch. Word of the lesson spreads quickly and I soon get a phone call from the head of the undergraduate research society at university faculty asking whether I could present the same lecture to eager undergraduate students during my lunchtime. I happily oblige and find myself lecturing another 100+ students that afternoon. Their enthusiasm and eagerness to grasp any learning opportunity that comes their way totally makes up for their lack of expertise. Nonetheless, they are soon analysing ECGs like total pros! I have a further two lectures scheduled during my two last weeks here at Panzi.

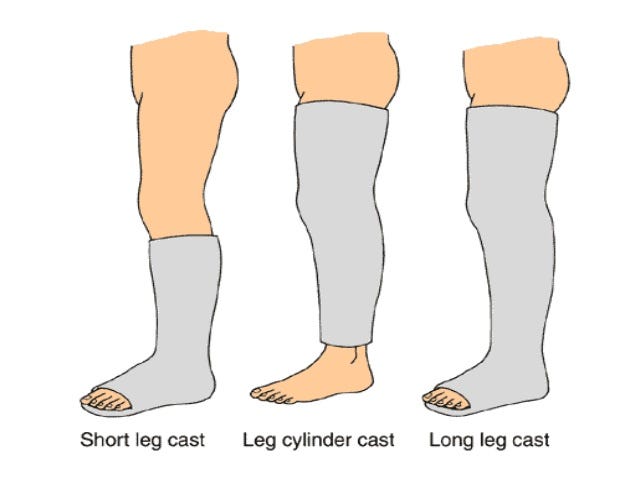

My frustration for this health system continues to grow daily as I repeatedly great a young boy with a long leg cast for an unstable tibial fracture walking the halls of the hospital. The footplate of his cast has completely eroded and it has ceased serving any purpose. After talking to the boy, the issue becomes evidently clear: his tibial fracture has long healed, yet he has had the cast on for almost three months (well passed the recommended 6 week period). Such patients are frequent here at Panzi and are colloquially known as “hospital prisoners”. The orthopaedic department is not allowed/refuses to remove casts until patients have settled their casting debt in full. This is completely unethical and results in patients walking around in half-broken casts for weeks on end confined to the hospital premises until they can afford to pay their medical bills. Furthermore, the young boy’s cast had started to cause pressure sores, potentially threatening the viability of his lower limb. Determined to resolve this issue, I strategically sit next to the orthopaedic surgeon on the hospital bus ride back home and politely confront him on the issue. Disgracefully, there is no way to sway his opinion and he refuses to remove the cast until the boy settles his debts. I’m appalled by his judgement and vow to remove the cast myself in the coming days.

During a haematology consult, I find myself taking the birth history of a middle-aged woman with severe anaemia accompanied by her mother. She had a complicated birth at the Fomulac district hospital back in 1987. I curiously ask her mother whether she possibly remembers the doctor who delivered her daughter. After a few confused seconds, she suddenly looks excited and proudly says that a “Mzungu (white) doctor” delivered her child and that her name was “Dr Mimi, Nini or something like that”. I can’t stop smiling and tell her that that Dr Nini is my mother. She looks at me in total bewilderment and a few seconds later she’s laughing and hugging me! What a pleasant coincidence.

The last case I have to share involves a patient who was admitted with a large pericardial effusion. After performing a pericardial tap and sending the fluid off for further analysis, the PCR results confirmed our suspicion for a rifampicin sensitive pericardial tuberculosis (a form of tuberculosis that affects the outer layer of the heart). This type of pathology being relatively rare here meant that the internal medicine team were unsure whether corticosteroids were indicated in these circumstances. I chose to highlight this case because it showcases the far reaching effects that the late professor Bongani Mayosi had throughout the world. The famous IMPI trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine answered this precise question. It was uplifting to see his research put into direct practice thousands of kilometres from South Africa in the middle of Africa.